Table of Contents

What is the relationship between nucleophilicity and leaving group ability?

Nucleophilicity describes how readily a species donates its electrons to form a new bond. It’s essentially a measure of how “electron-rich” a species is. Think of a nucleophile as a “bond seeker.” The more electron-rich a species is, the better its ability to donate electrons and form a new bond, making it a stronger nucleophile.

Leaving group ability refers to how easily a group departs from a molecule, taking its electrons with it. It’s essentially a measure of how “electron-poor” a group is. Imagine a leaving group as the “bond breaker.” The more electron-poor a group is, the easier it is for it to leave and take its electrons with it, making it a better leaving group.

So, how are these two concepts connected? Think of it like a game of tug-of-war:

Nucleophile: The stronger the nucleophile, the more it wants to “pull” on the electrons in a bond.

Leaving Group: The better the leaving group, the less it wants to “hold on” to the electrons in a bond.

A strong nucleophile can often be a poor leaving group, and vice versa. This is because a strong nucleophile has a strong desire to form new bonds, making it less likely to leave an existing bond. Conversely, a good leaving group prefers to be by itself and doesn’t want to form new bonds, making it less likely to be a good nucleophile.

Here’s a simple analogy:

Imagine you’re holding a ball (the bond) with a friend. A strong nucleophile is like someone who wants the ball badly and is willing to pull really hard to get it from you. A good leaving group is like someone who doesn’t really care about the ball and is happy to let go of it easily.

Let’s consider a couple of examples:

Hydroxide ion (OH–): Hydroxide is a strong nucleophile because it’s rich in electrons and wants to form new bonds. It’s a poor leaving group because it doesn’t want to leave its electrons behind.

Iodide ion (I–): Iodide is a good leaving group because it’s relatively electron-poor and happy to leave with its electrons. It’s a weaker nucleophile because it’s less likely to want to share electrons to form a new bond.

Understanding the relationship between nucleophilicity and leaving group ability is crucial for comprehending various reactions in organic chemistry, particularly substitution and elimination reactions.

Is a stronger nucleophile a better leaving group?

Think of it this way: In substitution and elimination reactions, the key is to favor the formation of a weaker base as a leaving group. Why? Because a weaker base is more stable and less likely to snatch back the carbon it just left.

To make this even clearer, consider an analogy: Imagine you’re trying to convince a friend to switch to a new phone. You might have a great new phone, but if your friend loves their old phone, they’re probably not going to switch. It’s the same with leaving groups. A strong nucleophile, like a good friend with a great phone, wants to hold onto its electrons!

So, a strong nucleophile might be a great friend with a great phone, but a weak base (like a less enthusiastic friend with a less exciting phone) would make a much better leaving group.

To illustrate this concept, let’s break down a common scenario:

Say you have a molecule where a good leaving group, like bromide ion (Br-), is attached to a carbon. A strong nucleophile, like hydroxide ion (OH-), comes along and wants to displace the bromide ion.

Now, let’s analyze the situation from the perspective of the leaving group:

– Bromide ion (Br-): A weaker base, it’s happy to leave the carbon and be on its own.

– Hydroxide ion (OH-): A stronger base, it’s eager to grab the carbon and form a bond.

Since the hydroxide ion is a stronger base, it’s more likely to attack the carbon and displace the weaker bromide ion. The reaction favors the formation of a weaker base as a leaving group, which explains why a strong nucleophile often leads to a smooth and efficient substitution or elimination reaction.

It’s a bit like playing a game of musical chairs – the weaker base (bromide ion) is more willing to leave the carbon chair, allowing the stronger base (hydroxide ion) to claim it.

What is the role of the leaving group in a nucleophilic reaction?

Let’s break down why leaving groups are so important in nucleophilic reactions. Imagine a chemical reaction like a game of tug-of-war. The nucleophile wants to “pull” onto the carbon atom, but the leaving group is holding on tight. A good leaving group is like a weak opponent—it easily lets go of the carbon, allowing the nucleophile to swoop in and win the “tug-of-war.”

The stability of the leaving group plays a big role in its ability to leave. Think of it this way: a stable molecule is content on its own, so it’s more likely to break away from the carbon. For example, a weak base, like a halide ion (like chloride or bromide), is a good leaving group because it’s stable on its own. It’s happy to go off and do its own thing.

On the other hand, a strong base, like a hydroxide ion (OH-), is a bad leaving group. It’s not as happy to be alone, so it’s more likely to stay attached to the carbon atom. This makes it harder for the nucleophile to attack.

The better the leaving group, the faster the reaction proceeds. This is because the formation of a carbocation is the rate-determining step of the reaction. A good leaving group makes this step happen faster, leading to a faster overall reaction.

What are the factors affecting the leaving group ability?

As electronegativity increases, the leaving group’s ability to leave also increases. Think of it this way: when an atom becomes more electronegative, it wants to hold onto electrons even more tightly. This means it’s less likely to share those electrons with the molecule it’s attached to. So, if we move across the periodic table, we’re essentially increasing the electronegativity of the leaving group. As a result, the bond between the leaving group and the molecule weakens, making it easier for the leaving group to “leave.”

Let me explain it in a more simplified way. Imagine you have a friend who loves to hold onto their belongings. They’re super electronegative! They don’t want to share their stuff with anyone. Now, imagine trying to borrow something from them. It’s going to be really hard, right? They’re not going to let go easily. It’s the same with leaving groups. If a leaving group is highly electronegative, it won’t want to share its electrons with the molecule it’s attached to, making it harder for the leaving group to detach.

But the opposite is true when a leaving group has low electronegativity. Imagine a friend who’s happy to share their belongings. They’re less electronegative. You’d have a much easier time borrowing something from them, wouldn’t you? It’s the same with leaving groups. If they have low electronegativity, they’re more willing to share their electrons and can detach more easily.

To sum it up, the more electronegative a leaving group is, the more likely it is to leave because it’s less willing to share its electrons. This is a key principle that helps us understand how reactions occur and what makes some leaving groups better than others.

Why does nucleophilicity increase down the group?

The electrons aren’t held as tightly to the nucleus as we go down a group. This means the electrons are more available to participate in reactions, making the atom a better nucleophile.

Let’s break this down:

Electronegativity is a measure of an atom’s tendency to attract electrons. As we go down a group, the atomic radius increases. The electrons in the outer shell are further from the nucleus and experience less attraction. This results in lower electronegativity.

Polarizability is another important factor. It’s the ability of an electron cloud to be distorted by an electric field. The larger the atom, the more polarizable it is. Think of it like a big, fluffy cloud versus a small, tightly packed one. The big cloud is easier to distort.

The larger, more polarizable atoms with lower electronegativity are more likely to donate their electrons. This is because they have a more loosely held electron cloud, making them better nucleophiles.

Here’s an example: Consider the halogens (fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine). Fluorine is the most electronegative and has the smallest atomic radius. Iodine has the lowest electronegativity and the largest atomic radius. Iodine is the most polarizable and therefore the best nucleophile among the halogens.

Let’s recap:

Electronegativity decreases down a group, making the electrons less tightly held.

Atomic radius increases down a group, increasing polarizability.

Increased polarizability leads to more loosely held electrons, making the atom a better nucleophile.

I hope this makes sense!

What is the leaving group ability proportional to?

A leaving group’s stability is often tied to its basicity. Stronger bases are generally poorer leaving groups because they are more likely to hold onto their electrons and re-bond with the molecule. Weaker bases are better leaving groups because they are less likely to hold onto their electrons, making them more willing to leave.

Here’s a simple way to understand it: imagine a group of friends at a party. Some friends are super social and always want to stick around (strong bases), while others are more independent and ready to leave whenever (weaker bases). The independent friends are the better leaving groups because they’re not holding onto the party (molecule) for dear life!

To visualize this, consider these examples:

Hydroxide (OH-) is a strong base and a poor leaving group. It’s very reactive and wants to grab onto a proton (H+). This means it’s likely to hang around and re-bond with the molecule, making it a poor leaving group.

Chloride (Cl-) is a weak base and a good leaving group. It’s relatively unreactive and more likely to leave the molecule because it’s happy on its own.

Remember: the stability of the leaving group is crucial for determining its ability to leave. And basicity is one key factor that affects this stability. The more stable the leaving group, the better it is at leaving!

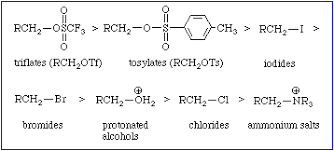

Is tosylate a better leaving group than iodide?

In some reactions, like when ethoxide acts as the nucleophile, tosylate shines as the superior leaving group. However, the story changes when you introduce a thiolate nucleophile. In this scenario, iodide and even bromide take the lead as the better leaving groups.

Why does this happen? It boils down to the interplay of factors like the stability of the leaving group and the nucleophile’s strength.

Tosylate is generally a good leaving group because it forms a stable anion. It’s able to handle the negative charge well.

Ethoxide is a relatively strong nucleophile, meaning it’s eager to attack and grab electrons. In this scenario, tosylate’s stability makes it a good partner, facilitating the reaction.

* However, thiolate is a much stronger nucleophile than ethoxide. It’s even more aggressive in its pursuit of electrons. This increased nucleophilicity changes the game. Iodide and bromide, while not as stable as tosylate, can better accommodate the thiolate’s powerful attack.

Think of it like this: tosylate is a sturdy, reliable partner, but iodide and bromide are more flexible and adaptable, allowing them to handle a more demanding partner.

So, while tosylate is a great leaving group in many situations, it’s not always the champion. The choice of the best leaving group depends on the specific nucleophile involved and the reaction conditions.

See more here: Is A Stronger Nucleophile A Better Leaving Group? | Nucleophilicity And Leaving Group Ability

What determines nucleophilicity and leaving-group ability?

A nucleophile is a species that loves to donate electrons. The better a nucleophile is at donating electrons, the more nucleophilic it is. This means that a nucleophile’s electron-donor capability is key to its strength. It’s all about the energy and shape of the atom’s nonbonding atomic orbital. A good way to think about it is that a nucleophile wants to share its electrons with an electron-deficient atom (like a carbon in a carbocation).

Now, leaving groups are a little different. They’re the groups that are “leaving” a molecule. A good leaving group is one that is stable on its own. The stronger the bond between the carbon and the leaving group, the weaker the leaving group. This means a good leaving group has a weak bond to the carbon it’s leaving.

Here’s why this is important: when a nucleophile attacks a molecule, it can replace a leaving group. A good nucleophile will readily donate its electrons to attack, and a good leaving group will happily break away from the molecule. This is a fundamental concept in organic chemistry, and understanding these factors will help you predict reaction outcomes and mechanisms.

Let’s dive a bit deeper into what influences electron-donor capability and bond strength.

Electron-donor capability: A nucleophile’s ability to donate electrons depends on several factors:

Charge: A negatively charged nucleophile is more likely to donate electrons. For example, hydroxide ion (OH-) is a stronger nucleophile than water (H2O) because it has a negative charge.

Electronegativity: Less electronegative atoms are better electron donors. For example, iodine (I-) is a better nucleophile than fluoride (F-) because iodine is less electronegative and therefore “holds” its electrons less tightly.

Size: Larger nucleophiles are generally better nucleophiles. This is because larger atoms have more diffuse nonbonding atomic orbitals, making it easier to share electrons.

Bond strength: The strength of the carbon-leaving group bond is largely determined by the leaving group’s stability:

Stability: A leaving group that can stabilize a negative charge is a good leaving group. Think about it, a good leaving group doesn’t want to be attached to the carbon anymore, so it will be happier (more stable) if it can hold the negative charge on its own. Common good leaving groups like halides (Cl-, Br-, I-) can stabilize the negative charge by spreading it out over their larger atomic size.

Resonance: Leaving groups that can stabilize their negative charge through resonance are especially good leaving groups. Take carboxylates for example, they can stabilize their negative charge through resonance delocalization.

So, next time you encounter a reaction with nucleophiles and leaving groups, remember that electron-donor capability and bond strength are the key players determining how readily the reaction will occur. It’s all about understanding the forces that drive these reactions.

How is nucleophilicity determined?

It all boils down to how well a nucleophile can donate electrons. The electron-donor capability of a nucleophile is key. This capability depends on a few things, including the energy and shape of the X − np atomic orbital. Imagine it like this: The more easily a nucleophile can share its electrons, the stronger its nucleophilicity.

Now, let’s talk about the leaving group. This is the atom or group of atoms that departs from a molecule during a reaction. The leaving-group ability is directly related to how strong the bond is between the carbon and the leaving group (Y). A weaker bond means the leaving group is more likely to depart, making the reaction more favorable.

Think of it like this: The more easily a leaving group can leave, the more likely the reaction is to proceed.

Understanding Electron-Donor Capability:

The electron-donor capability, or nucleophilicity, of a molecule depends on several factors:

Electronegativity: A more electronegative atom will hold its electrons more tightly, making it less likely to donate them. For example, fluorine is more electronegative than oxygen, so fluoride ion is a weaker nucleophile than hydroxide ion.

Size: A larger atom will have a more diffuse electron cloud, making it easier to donate electrons. For example, iodide is a better nucleophile than fluoride because iodine is a larger atom.

Charge: A negatively charged atom is more likely to donate electrons than a neutral atom. For example, hydroxide ion is a better nucleophile than water.

Understanding Leaving Group Ability:

A good leaving group is a species that is stable on its own. Here’s why:

Stability: A stable leaving group is less likely to recombine with the molecule it left, making the reaction more likely to proceed. Good leaving groups often have a negative charge or are capable of delocalizing the charge through resonance.

Bond Strength: A weaker bond between the carbon and the leaving group makes it easier for the leaving group to depart.

Putting it Together

A strong nucleophile with a good leaving group is a recipe for a successful nucleophilic reaction! The more readily a nucleophile can donate electrons and the more easily a leaving group can depart, the faster the reaction will proceed.

Why does a good leaving group speed up a nucleophile reaction?

A good leaving group is essentially a stable molecule or ion that readily breaks away from the carbon atom, leaving behind a positive charge. This happens because the leaving group has a strong desire to leave and becomes more stable on its own. So, the stronger the leaving group’s desire to leave, the faster it breaks the carbon-leaving group bond, and the faster the entire reaction proceeds.

Think of it this way: imagine a team of runners. The leaving group is the weakest runner. If the leaving group is a good leaving group, it’s a strong runner and can leave the team easily. This allows the rest of the team (the carbocation) to move forward more quickly. If the leaving group is a weak leaving group, it’s a slow runner and struggles to leave the team. This slows down the entire team, and the reaction proceeds at a much slower rate.

Here’s a breakdown of how the stability of the leaving group impacts its ability to leave:

Weak Bases:Leaving groups that are weak bases are better leaving groups. This is because they are more stable in their deprotonated form. For example, halides like bromide (Br-) and iodide (I-) are good leaving groups because they are weak bases.

Electron-Withdrawing Groups:Leaving groups that have electron-withdrawing groups are also good leaving groups. This is because these groups stabilize the negative charge that develops on the leaving group when it departs. For example, tosylate (OTs-) is a good leaving group because it has an electron-withdrawing sulfonyl group.

Good Leaving Groups: Examples of good leaving groups include halides (bromide, iodide, chloride), sulfonate esters (tosylate, mesylate), alcohols, carboxylic acids, and water.

In contrast, poor leaving groups are those that are strong bases or lack electron-withdrawing groups. They don’t readily leave the molecule and tend to slow down the reaction. Examples of poor leaving groups include hydroxide (OH-), alkoxide (RO-), and amide (NH2-).

Can a species be both a good nucleophile and a leaving group?

Let’s break it down: Nucleophilicity is all about how readily a species attacks a positive center, like the carbon in a molecule. A good nucleophile is a quick attacker, and it’s often a species with a negative charge or a lone pair of electrons it can share.

Leaving groups, on the other hand, are groups that detach from a molecule. A good leaving group is stable on its own and doesn’t want to stick around. It’s often a weak base.

Now, how can a species be both? Well, the key is understanding that the terms “good” and “bad” are relative. It depends on the specific reaction conditions. Take iodide, for instance. It’s a good nucleophile due to its negative charge and large size. But, the carbon-iodine bond is relatively weak, making iodide a good leaving group too.

Think of it like this: iodide can be a forceful attacker (nucleophile) in some situations, but it can also be easily pushed away (leaving group) in other situations.

Here’s an example: Let’s say we’re looking at a reaction involving iodide and a molecule with a good leaving group. In this case, the iodide will act as a nucleophile, attacking the molecule and kicking out the existing leaving group. But, if we change the reaction conditions, like using a different solvent or adding a stronger nucleophile, the iodide might then become the leaving group, being replaced by the more powerful attacker.

So, the trick is to consider the specific reaction conditions and the relative reactivity of the species involved. A species might be a good nucleophile in one situation, but a good leaving group in another!

See more new information: musicbykatie.com

Nucleophilicity And Leaving Group Ability: A Powerful Duo

Okay, so let’s talk about nucleophilicity and leaving group ability, two crucial concepts in organic chemistry. They’re kinda like the yin and yang of reactions. Think of it this way: nucleophiles are like the attackers, and leaving groups are like the defenders. They’re always playing a game of tug-of-war, and the outcome of this game determines whether a reaction happens or not.

Nucleophiles – The Attackers

First, let’s tackle nucleophiles. They’re basically electron-rich species that are attracted to positively charged centers. Think of them as hungry little molecules looking for a place to donate their electrons.

Now, you might be wondering, what makes a good nucleophile? Well, there are a few factors that play into it:

Charge: Negatively charged species are usually better nucleophiles than neutral ones. They’re just bursting with electrons, making them super eager to attack!

Electronegativity: The more electronegative an atom is, the less likely it is to be a good nucleophile. Think of it like this: the more electronegative an atom is, the tighter it holds onto its electrons. This makes it harder for it to share those electrons with another molecule.

Steric Hindrance: Sometimes, nucleophiles can be bulky. This can make it difficult for them to approach a target molecule, slowing down the reaction.

Solvent: The solvent can also influence nucleophilicity. Polar protic solvents like water can actually decrease nucleophilicity by solvating the nucleophile, making it less reactive.

Leaving Groups – The Defenders

Now let’s shift our focus to leaving groups. These are the molecules that detach themselves from a molecule during a reaction. Think of them as the defenders, trying to hold on to their electrons.

Here’s what makes a good leaving group:

Stability: The more stable a leaving group is, the better it is at leaving. Why? Because stable leaving groups are happy on their own. They don’t want to hang around and be attached to another molecule.

Weak Base: A good leaving group is a weak base. This means it’s not particularly good at accepting a proton. This is important because a strong base would prefer to stay attached to the molecule and not leave.

How Nucleophilicity and Leaving Group Ability Work Together

Let’s put these concepts together. In a reaction, the nucleophile will attack a molecule, usually at a positively charged center, and this causes the leaving group to detach. But remember, the leaving group wants to stay attached! The battle between the nucleophile and the leaving group determines whether the reaction will happen and how fast it will proceed.

Key Factors Influencing Nucleophilicity and Leaving Group Ability

Let’s dive a bit deeper into the factors that influence nucleophilicity and leaving group ability.

Nucleophilicity

Atom: Nucleophilicity increases down a column of the periodic table. For example, iodine is a better nucleophile than fluorine. This is because the iodine atom is larger and has more diffuse electrons.

Hybridization:Nucleophilicity decreases as the hybridization of the attacking atom changes from sp3 to sp2 to sp. For example, an alkoxide ion (sp3) is more nucleophilic than an enolate ion (sp2).

Solvent:Nucleophilicity is usually higher in polar aprotic solvents. These solvents are less able to solvate the nucleophile, allowing it to be more reactive.

Leaving Group Ability

Stability: The more stable the leaving group is, the better it will be at detaching from a molecule.

Resonance:Leaving groups that can delocalize their negative charge through resonance are more stable and therefore better leaving groups.

Inductive Effect:Leaving groups with electron-withdrawing groups attached to them are more stable and better leaving groups.

Examples

Let’s look at some examples to solidify our understanding:

SN2 Reactions: In SN2 reactions, a nucleophile attacks an electrophile and displaces the leaving group. The rate of the reaction is influenced by the nucleophilicity of the attacking species and the leaving group ability of the leaving group.

Acid-Base Reactions: In acid-base reactions, the base acts as a nucleophile, attacking the acidic proton. The ability of the proton to be removed depends on the strength of the leaving group – the conjugate base of the acid.

FAQs

1. What’s the difference between a nucleophile and a base?

A nucleophile is any species that donates an electron pair to form a bond. A base is a substance that accepts a proton. All bases are nucleophiles, but not all nucleophiles are bases.

2. How can I tell if a molecule is a good leaving group?

A good leaving group is usually a weak base, stable, and can delocalize its negative charge through resonance or inductive effects.

3. Can a good leaving group be a good nucleophile?

It’s possible, but it’s not common. A good leaving group is usually a weak base and therefore not a good nucleophile.

4. What are some common examples of nucleophiles and leaving groups?

Here are a few examples:

Nucleophiles: Hydroxide ion (OH-), alkoxide ions (RO-), amines (RNH2), halides (Cl-, Br-, I-), cyanide ion (CN-), water (H2O)

Leaving Groups: Halides (Cl-, Br-, I-), tosylate (OTs-), mesylate (OMs-), water (H2O)

5. Why is it important to understand nucleophilicity and leaving group ability?

Understanding nucleophilicity and leaving group ability is essential for predicting reaction outcomes and designing new synthetic strategies.

Let me know if you have any more questions!

Nucleophilicity and Leaving-Group Ability in

A clear picture emerges from these analyses: nucleophilicity is determined by the electron-donor capability of the nucleophile (i.e., energy and shape of the X − np atomic orbital), and ACS Publications

Leaving Groups – Chemistry LibreTexts

Resonance Increases the Ability of the Leaving Group to Leave: As we learned previously, resonance stabilized structures are weak bases. Therefore, leaving Chemistry LibreTexts

Effects of Solvent, Leaving Group, and Nucleophile on

Effects of Leaving Group. An S N 1 reaction speeds up with a good leaving group. This is because the leaving group is involved in the rate-determining step. A good Chemistry LibreTexts

Nucleophile – Chemistry LibreTexts

Now that we have determined what will make a good leaving group, we will now consider nucleophilicity. That is, the relative strength of the nucleophile. Chemistry LibreTexts

Nucleophilicity and leaving-group ability in frontside and backside

A clear picture emerges from these analyses: nucleophilicity is determined by the electron-donor capability of the nucleophile (i.e., energy and shape of the X(-) np PubMed

Nucleophilic Substitution (SN2): Dependence on

They found that the nucleophilicity is determined by the electron-donor capability of the nucleophile (energy and shape of the X − np atomic orbital), and the leaving-group ability is derived directly Chemistry Europe

What makes a good leaving group? – Master Organic

A leaving group is a nucleophile acting in reverse; it accepts a lone pair as the bond between it and its neighbor (usually carbon for our purposes) is broken. So what makes a good leaving Master Organic Chemistry

A Unified Framework for Understanding

The concepts of nucleophilicity and protophilicity are fundamental and ubiquitous in chemistry. A case in point is bimolecular nucleophilic substitution (S N 2) and base-induced elimination (E2). Chemistry Europe

S N 2: Electrophile, Leaving Group, and Nucleophile

In an S N 2 reaction, the nucleophile approaches the electrophile from the side opposite to the leaving group. This means that the three other groups attached to CHEM123 chirp

Leaving Groups – Organic Chemistry | Socratic

The general idea is that “poor” leaving groups have a strong nucleophilicity, or a strong “desire” to not bring its electrons with it and allow the bond to break. For example, #I^-# Socratic

Nucleophiles, Electrophiles, Leaving Groups, And The Sn2 Reaction

Nucleophilic Strength

Leaving Group Stability – Sn1 And Sn2 Reactions

Nucleophilic Strength

Nucleophilicity Comparison Trick Organic Chemistry | Iit Jee \U0026 Neet | Vineet Khatri | Atp Star Kota

Basicity Vs Nucleophilicity – Steric Hindrance

Sn2 Leaving Group Ability And Nucleophilicity | Organic Chemistry Lessons

Nucleophiles And Electrophiles

Link to this article: nucleophilicity and leaving group ability.

See more articles in the same category here: https://musicbykatie.com/wiki-how/